The “Comey Standard” for Espionage Act and 18 U.S.C. § 1924 Violations and What It Could Mean for Comey Himself

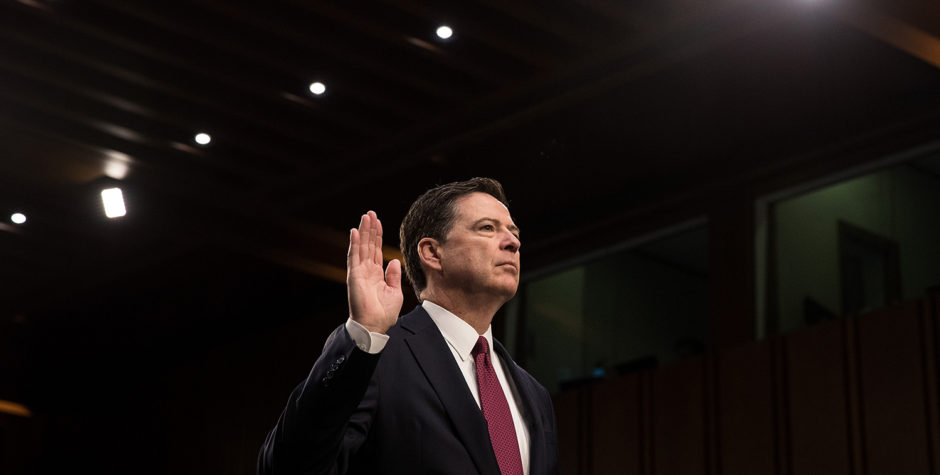

“There’s a thing called mens rea.” – Fired FBI Director James Comey

If fired FBI Director James Comey leaked or mishandled classified information, the “Comey Standard” that infamously led to his “no charges are appropriate” recommendation for Hillary Clinton may, ironically, be Comey’s own undoing.

Here’s how.

As we reported last month, in his testimony under oath to a U.S. Senate committee, Comey admitted to leaking at least one memo about his confidential and privileged deliberative conversations with the President. And, according to new reports, four of the seven memos Comey drafted contained classified information and “had markings making clear they contained information classified at the ‘secret’ or ‘confidential’ level.”

We do not yet know whether the memo Comey admitted to leaking was one of the four containing classified information. We also do not yet know whether Comey leaked other memos beyond the one he admitted to or if he leaked any other classified information connected to the conversations he memorialized.

But one thing we do know is that if Comey leaked or mishandled classified information, it’s not just his June 2017 congressional confession that he was a leaker that will be damning in his prosecution.

Go back to July 7, 2016, when Comey testified before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform and notoriously attempted to defend and rationalize his decision to not recommend charges against Hillary Clinton in connection with her “extremely careless” handling of classified information on her private email servers.

What he said then provides damaging “clear evidence,” to use his words, that he knew about the law criminalizing the mishandling of classified information, what type of conduct violates that law, and that he possesses the very knowledge he claimed Hillary Clinton did not have. Here is what Comey testified under oath back then:

In our system of law, there’s a thing called mens rea. It’s important to know what you did, but when you did it, this Latin phrase “mens rea” means, what were you thinking? And we don’t want to put people in jail unless we prove that they knew they were doing something they shouldn’t do. That is the characteristic of all the prosecutions involving mishandling of classified information.

There is a statute that was passed in 1917 that, on its face, makes it a crime, a felony, for someone to engage in gross negligence. So that would appear to say: Well, maybe in that circumstance, you don’t need to prove they knew they were doing something that was unlawful; maybe it’s enough to prove that they were just really, really careless, beyond a reasonable doubt.

At the time Congress passed that statute in 1917, there was a lot of concern in the House and the Senate about whether that was going to violate the American tradition of requiring that, before you’re going to lock somebody up, you prove they knew they were doing something wrong, and so there was a lot of concern about it. The statute was passed. As best I can tell, the Department of Justice has used it once in the 99 years since, reflecting that same concern. I know, from 30 years with the Department of Justice, they have grave concerns about whether it’s appropriate to prosecute somebody for gross negligence, which is why they’ve done it once that I know of in a case involving espionage.

The “statute that was passed in 1917” Comey references is an Espionage Act provision now codified as 18 U.S.C. § 793(f). This section makes it a felony to mishandle classified information with “gross negligence” – a lower standard than, say, knowingly or willfully. But Comey disapproves prosecution under this statute altogether because “we don’t want to put people in jail unless we prove that they knew they were doing something they shouldn’t do.”

But there’s a separate criminal code section Comey discussed that day, 18 U.S.C. § 1924, which makes it a misdemeanor to knowingly mishandle classified information. Comey apparently disapproves prosecutions under that section unless he is convinced the offender “clearly knew they were breaking the law.” To Comey, “[s]o should have known, must have known, had to know, does not get you there. You must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that they knew they were engaged in something that was unlawful.”

Setting aside for now the accuracy of Comey’s questionable and convoluted treatment of mens rea jurisprudence or even the propriety of him imposing his own value judgment to nullify the express will of Congress, what is clear from his testimony is that Comey (1) knows both the Espionage Act and 18 U.S.C. § 1924 exist; (2) knows what the laws require; (3) believes that if someone knows the law exists and then violates that law by mishandling classified information, the law is plainly violated; and (4) believes such a knowing violation justifies prosecution.

That could spell trouble for Comey. With the recent revelation that four of his seven memos contained classified information, and given his sworn statements describing his knowledge of the laws criminalizing mishandling of classified information (and his opinion that prosecution should be reserved for those who know about the law), Comey’s July 2016 testimony satisfies the Comey Standard if he in fact mishandled or leaked classified information in connection with those memos, or otherwise for that matter.

Comey clearly does not like § 793(f)’s criminalization of “gross negligence” and believes Espionage Act prosecutions should be reserved for people who know about the law when they violate it. Never mind the actual words Congress chose. Comey would not recommend prosecution unless there is clear evidence the person knew what they were doing was unlawful – whether under the Espionage Act’s “gross negligence” or § 1924’s “knowingly” standards. But his testimonial opining does more than give us a glimpse into his progressive jurisprudential philosophy, it makes it abundantly clear that he knows about these laws and what they prohibit. And under his own standard, it is precisely that knowledge that bridges the gap between why he did not recommend charges against Clinton then and why Comey himself could be charged now.

Put simply, he testified to the precise mental culpability that he determined Hillary Clinton lacked. His testimony satisfies the very concerns and disfavor he voiced about prosecutions under those laws for conduct that was not intentional. He described in painstaking detail the conduct and mental state he believed necessary to violate these laws and justify, in his view, a prosecution. And, setting lingual acrobatics aside, Comey testified to his knowledge of the laws and what they require, and that knowledge satisfies the “Comey Standard” for Espionage Act and § 1924 prosecutions.

If Comey leaked or mishandled classified information, based on his own sworn testimony, it was not just, to use his words, “extremely careless” and it was not even mere, to use the Espionage Act’s words, “gross negligence.” No, his testimony would be “clear evidence” (his words again) that he knew what he was doing was a crime. So, if he actually mishandled or leaked the information news reports now say was classified, according to the Comey Standard, a “reasonable prosecutor” would, in fact, bring that case.

That is the Comey Standard, and it may come back to bite him.