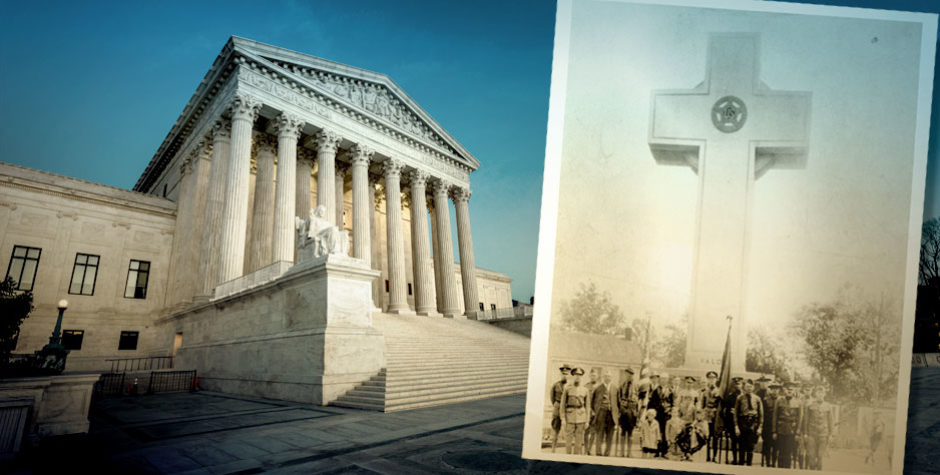

Supreme Court Hears Arguments on Bladensburg Peace Cross

This week, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case involving the Peace Cross, a monument erected nearly 100 years ago in Bladensburg, Maryland to honor 49 service members who gave their lives in World War I. This case, explained in greater detail here and here, will not only decide the fate of a veteran’s war memorial that has stood for nearly a century, it could shape the future of other war memorials, as well as religious displays generally, throughout the country.

On behalf of Lt. General Robert R. Blackman (Ret.), and over 230,000 ACLJ members, we filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court in support of the Peace Cross and the 49 local war heroes it commemorates.

Our brief made three overarching points: (1) the Court should formally overrule a 1971 Supreme Court decision (Lemon v. Kurtzman) that has been criticized and reviled for decades, and has only been sparingly used by the Supreme Court itself; (2) future challenges under the Establishment Clause should be evaluated using the two criteria recently applied by the Court in Town of Greece v. Galloway (historical practices and coercion); and (3) the Court should reject the theory, never adopted by the Supreme Court itself, that mere disagreement, objection, or hurt feelings can constitute an “injury in fact” under the Establishment Clause (“offended observer” standing).

During Wednesday’s arguments, many of the Justices asked probing questions of both sides regarding these three very points. Justice Gorsuch, referring to the Lemon decision as a “dog’s breakfast,” asked, “[i]s it time for this court to thank Lemon for its services and send it on its way?”

When the attorney for the American Humanist Association (“AHA”) tried explaining that Lemon remained a useful case, Justice Kavanaugh asked, “how can it be useful when we haven’t used it in the most important cases that are on point here . . . . If the test isn’t being used, that would suggest that the test doesn’t work for this context.”

On the subject of what factors should be used in deciding Establishment Clause cases, such as the Peace Cross at issue here, Chief Justice Roberts brought up an amicus brief by the eminent legal scholar, Michael McConnell, who wrote that, as an historical matter, the Establishment Clause prohibits “six things,” including “the government establishing a church,” “requiring people to pay for the church,” and “imposing burdens on people who don’t believe.”

As we pointed out in our own brief, quoting Judge Easterbrook of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals:

Standards such as those found in Lemon . . . and the “no endorsement” rule, not only are hopelessly open-ended but also lack support in the text of the first amendment and do not have any historical provenance. They have been made up by the Justices during recent decades. The actual Establishment Clause bans laws respecting the establishment of religion—which is to say, taxation for the support of a church, the employment of clergy on the public payroll, and mandatory attendance or worship.

Justice Alito, looking to the real-life consequences of what would happen if the Court held that the Peace Cross is unconstitutional, asked, “there are cross monuments all over the country, many of them quite old. Do you want them all taken down?” When the AHA attorney replied that “there’s a lot of exaggeration and distortion going on,” Justice Alito pointedly retorted, “So which ones do you think can stand?”

Finally, on the subject of “offended observer” standing, Justice Gorsuch nicely laid out the grounds why federal courts shouldn’t be hearing Establishment Clause challenges where the only so-called “injury” is based solely on hurt feelings:

There aren’t many places in the law where we allow someone to make a federal case out of their offensiveness about a symbol being “too loud” for them. We accept that people have to sometimes live in a world in which other people’s speech offend them. We have to tolerate one another.

This is the only area I can think of like that where we allow people to sue over an offense because, for them, it is “too loud.” And we get into, as a result, having to dictate taste with respect to displays.

We have a Ten Commandments display just above you, which may be “too loud” for many.

Why shouldn’t we apply our normal standing rules and require more than mere offense to make a federal case out of these?

Based on this week’s oral arguments, we are optimistic that the Peace Cross will be saved, and the efforts by those who want to see it torn down will ultimately be defeated. What remains to be seen, however, is how broadly or narrowly the Court will decide the case. A decision upholding the Cross based solely on the fact that it’s been in existence for over 90 years, as Justice Breyer hinted at during the argument, would do precious little to define the scope of the Establishment Clause moving forward.

As we argue in our amicus brief, it’s time for the Court to do one of two things: either (1) repudiate, root and branch, the unconstitutional theory of “offended observer” standing, or (2) overrule Lemon, and adopt in its place the two-fold approach used by the Court in Town of Greece, which looked to historical practices and coercion. As the Eighth Circuit recently held, upholding the national motto, “In God We Trust,” on national currency: “This two-fold analysis is complementary: historical practices often reveal what the Establishment Clause was originally understood to permit, while attention to coercion highlights what it has long been understood to prohibit.”

Should the Court decide the case using one of the rationales laid out in our brief, it will be a significant victory for the cross, our country, and the Constitution.

A decision is expected by the end of June.