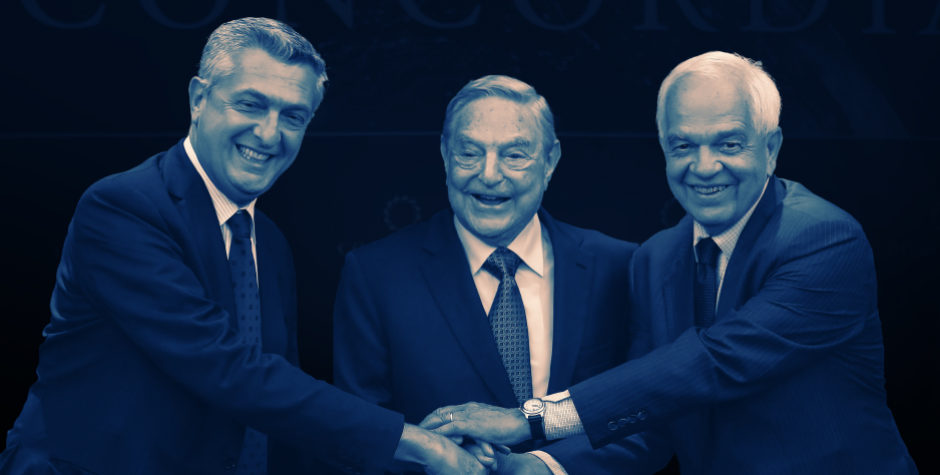

Exposing Conflicts of Interest Between George Soros-Funded NGOs and Judges on the European Court of Human Rights – Part 2

ACLJ Note: The following report is the second in a three-part series by our European affiliate, the European Centre for Law and Justice (ECLJ), exposing the extreme bias of the judges of the European Court of Human Rights.

In the first installment, we discussed the relationships between the judges of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and leading, George Soros-funded non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and what should the Court be doing about them, particularly in cases in which doubts about the judges’ impartiality might arise.

In order to apply the impartiality standard of the Court to its own judges, we may take the example of Mr. Yonko Grozev, the current Bulgarian judge. Grozev was previously the founding member of the Helsinki Committee of Bulgaria (1992-2013), as well as a member of the board of the Open Society Institute of Sofia (2001-2004) and then of the Open Society Justice Initiative (New-York) from 2011 until his election at the Court. In this capacity, he brought several cases before the ECtHR, such as the infamous “Pussy Riot” case (Mariya Alekhina and Others v. Russia, no. 38004/12, 17 July 2018) which was still pending when he eventually became a judge in April 2015.

It is obvious that such a lawyer has strong experience with the human rights system. The problem arises when one observes that, once elected judge, he adjudicated in cases introduced in 2014 and 2015 by the same Helsinki Committee of Bulgaria on which he’d been a founding member (see D.L. c. Bulgarie, n° 7472/14, 19 May 2016. Aneva and Others v. Bulgaria, n° 66997/13, 77760/14 et 50240/15, 6 April 2017). Clearly this raises an issue of impartiality and any judge in that position should have withdrawn.

In another case, still pending, Grozev sat while the Open Society Justice Initiative intervened as a third party in the case (see the proceedings before the Grand Chamber of Big Brother Watch and Others v. United-Kingdom, n° 58170/13).

The purpose here is not to single out Mr. Grozev, as 18 out of the 22 judges concerned had the same conflicts of interest. Nor is the issue here that Judge Grozev exhibited genuine bias towards one of the parties, but that the appearance of such bias can be said to exist.

One may question whether the risk of impartiality also exists when the NGO is not an applicant, but a third party. In order to answer this, consider the fact that NGOs almost always intervene in support of one of the parties, generally the applicant, and that their interventions can carry real weight in the final decision.

The risk of partiality of the judges because of third party interventions also exists. It should be noted in this regard that, in its provisions relating to incompatibilities, the Rules of Procedure of the Court do not distinguish between the two modes of action and forbids any former judge to “represent a party or third party in any capacity in proceedings before the Court” before the expiration of a period of two years after the end of their mandate (Article 4 of the European Convention on Human Rights).

This is precisely what happened in the British precedent of Lord Hoffmann in the famous Pinochet case. After the House of Lords ruling in November 1998 that Mr. Pinochet could not enjoy immunity from prosecution, in which Lord Hoffmann had participated, it emerged that Lord Hoffmann was an unpaid director of Amnesty International Charity Ltd, whereas Amnesty International intervened in the case in support of the extradition of Mr. Pinochet.

Lord Hoffmann’s wife had also been employed by the group for 20 years. Following this revelation, the ruling was set aside by the House of Lords (R v Bow Street Metropolitan Stipendiary Magistrate, ex parte Pinochet Ugarte (No 2). Eventually, when the case was adjudicated again by other judges, their ruling was completely different from the first ruling.

Lord Browne-Wilkinson explained that “once it is shown that the judge is himself a party to the cause, or has a relevant interest in its subject matter, he is disqualified without any investigation into whether there was a likelihood or suspicion of bias. The mere fact of his interest is sufficient to disqualify him unless he has made sufficient disclosure”.

Applying those principles to the situation at stake, he declared that “in the special circumstances of this case, including the fact that Amnesty International was joined as an intervener and appeared by counsel before the appellate committee, Lord Hoffmann, who did not disclose his links with Amnesty International, was disqualified from sitting”.

Rightly so.

Following the publication of the report of the ECLJ, the Minister of Justice of Bulgaria, Danail Kirilov, made a public statement in which he expressed his concern about the situation revealed by the ECLJ report. "We have come to the point where this time it is French lawyers who are informing us about the situation in Bulgaria," he explained. According to Kirilov, such a lawyer should not be able to be appointed as a judge there. He added that Grozev could be dismissed following a revelation such as the European Centre for Law and Justice’s exposé.

In the final instalment of this series, we will discuss more recusal issues and potential solutions to this problem.

Read the ECLJ’s full report, "NGOs and the Judges of the ECHR, 2009 –2019" here.