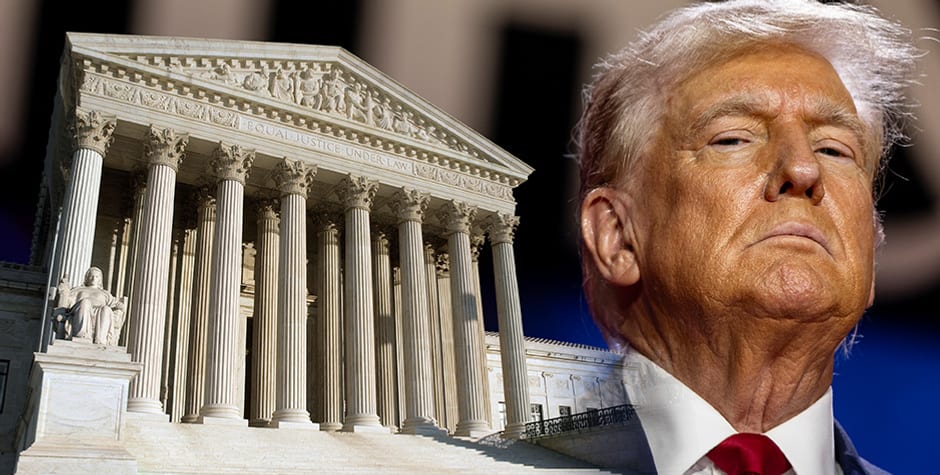

Supreme Court Agrees With the ACLJ and Rules Presidents Entitled to Immunity From Criminal Prosecution for Official Acts in Office in Major Blow to Jack Smith’s Prosecution of Trump

Listen tothis article

The U.S. Supreme Court issued a major ruling regarding the scope of presidential immunity, agreeing with our amicus brief that Presidents are entitled to immunity from criminal prosecution for official acts in office. Special Counsel Jack Smith had delivered an indictment against President Trump, charging him based on his speeches and conduct as President of conspiring to defraud the United States and attempting to obstruct an official proceeding. Then the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Trump could not claim presidential immunity for his actions while President. The Supreme Court has now reversed that ruling, holding that a former President has a presumption of immunity for official acts in a 6-3 decision.

We filed a crucial amicus brief in support of presidential immunity to defend not only Trump but also every President, past, present, and future. A President cannot be subject to legal charges after they leave office for actions taken in their official capacity as President of the United States. Otherwise, it will open up a firestorm of cases against former Presidents. We explained in our brief:

A President should be immune from criminal prosecution for his official acts undertaken during his term of office. And the deleterious impact of potential criminal exposure for official acts applies just as much on 11:59 AM on January 20 as it does at 12:00 PM. Former Presidents must be immune for official acts upon their exit from the presidency just as they were while still in office. That such vital immunity could meaningfully exist and then vanish with the tick-tock of the second hand is absurd. It also does not meaningfully exist if it applies only in civil courts and not in criminal. This holds true for any President, of any party, and its implications stretch far beyond the results of this case.

As we emphasized in our brief, presidential immunity is crucial to ensuring that all Presidents are protected. The legal doctrine of presidential immunity covers actions of the President that relate to official duties of the office, which protects Presidents from personal liability after they become a private citizen again – they have immunity.

The Supreme Court ruled, with Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson dissenting, that the Constitution’s structure entitles the President to presumptive immunity from prosecution for official acts. The Supreme Court also ruled that the President has absolute immunity from prosecution for their core constitutional powers (e.g., appointing ambassadors).

The Court did not draw the line for every action between official and unofficial, explaining that “the lower courts rendered their decisions on a highly expedited basis” and “did not analyze the conduct alleged in the indictment to decide which of it should be categorized as official and which unofficial” – and it wasn’t briefed before the Supreme Court. The effect of the decision, therefore, is to send the case back to the lower courts to determine which acts by President Trump were official and which were unofficial.

The Supreme Court concluded, in an opinion by Chief Justice Roberts:

The President enjoys no immunity for his unofficial acts, and not everything the President does is official. The President is not above the law. But Congress may not criminalize the President’s conduct in carrying out the responsibilities of the Executive Branch under the Constitution. And the system of separated powers designed by the Framers has always demanded an energetic, independent Executive. The President therefore may not be prosecuted for exercising his core constitutional powers, and he is entitled, at a minimum, to a presumptive immunity from prosecution for all his official acts. That immunity applies equally to all occupants of the Oval Office, regardless of politics, policy, or party.

That conclusion is crucial to ensure that the President’s authority is not improperly curtailed. The Supreme Court made clear “that under our constitutional structure of separated powers, the nature of Presidential power requires that a former President have some immunity from criminal prosecution for official acts during his tenure in office.”

The Supreme Court held that certain allegations in the indictment were, on their face, official acts. Specifically, the Supreme Court held that the meetings between Trump and the acting Attorney General to discuss investigating election fraud were, on their face, purely official acts: “[T]he President cannot be prosecuted for conduct within his exclusive constitutional authority. Trump is therefore absolutely immune from prosecution for the alleged conduct involving his discussions with Justice Department officials.”

The Court also notes in a footnote that the District Court, “if necessary,” should consider whether two of the charges brought by Jack Smith against Trump in Washington, involving the obstruction of an official proceeding, can even go forward in light of the Court’s ruling last week in Fischer v. United States, narrowing the scope of that law. (See our discussion of that case in which the Court also agreed with our amicus brief.) The Court also indicates that the President’s immunity for official acts “extends to the outer perimeter of the President’s official responsibilities, covering actions so long as they are not manifestly or palpably beyond his authority.” And in determining what is or is not official conduct, “courts may not inquire into the President’s motives.”

The Court did not make a final decision regarding the other allegations in the indictment, such as President Trump’s alleged pressure against Vice President Pence, or his conversations with state officials, or his conduct on January 6 itself, and instead remands “to the District Court to determine in the first instance—with the benefit of briefing we lack—whether Trump’s conduct in this area qualifies as official or unofficial.”

Justice Thomas also wrote a scathing concurring opinion in which he questioned the validity of Jack Smith’s appointment as Special Counsel: “If this unprecedented prosecution is to proceed, it must be conducted by someone duly authorized to do so by the American people.” He also highlighted how dangerous the prosecution here was: “Few things would threaten our constitutional order more than criminally prosecuting a former President for his official acts. Fortunately, the Constitution does not permit us to chart such a dangerous course.” Justice Barrett authored a concurrence, agreeing with the rest of the decision “that the Constitution prohibits Congress from criminalizing a President’s exercise of core Article II powers and closely related conduct,” but arguing that the issue, rather than framed as immunity, should be instead framed as whether criminal statutes can constitutionally be applied to official acts.

Abandoning immunity would have a chilling effect on the decision-making process of whoever occupies the Oval Office. Every national security or policy decision that involves the well-being of Americans would be made by a President worried about a possible post-presidency prosecution – forever changing how a President would do their job. This victory represents a major victory for the American people and the separation of powers. Moving forward, it will ensure that the structure of powers is properly maintained.

The ACLJ will continue to steadfastly defend the Constitution, fight against government overreach and over prosecution, and ensure that our constitutional republic endures.