“Offended Observers” Strike the Oakland Zoo

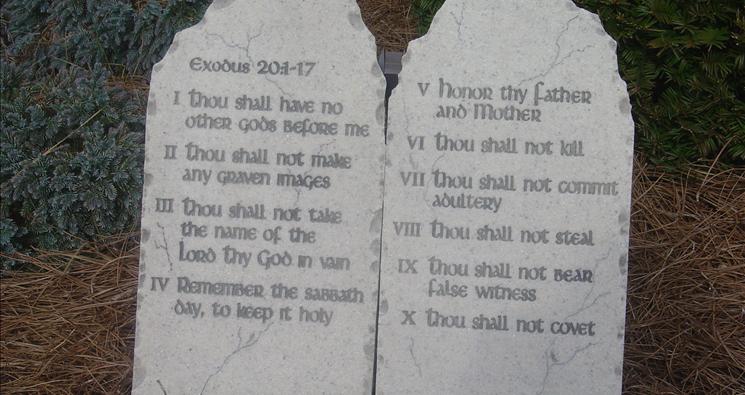

Over the holiday weekend I saw that angry activists never rest. In a Saturday letter, an activist claiming to represent “freedom of religious choice” and “equality” wrote the Oakland Zoo demanding that it remove a Ten Commandments display. To describe the letter as “overheated” would be an understatement. In a screed that conjures up slavery and legal segregation, the activist declares:

I am appalled at the imbalance of justice and the inequality displayed by the City of Oakland for favoring and condoning only this Christian monument on this public property; as it is insulting to the constitutional choice and lifestyle of alternative beliefs of any other citizens who are not adherents to Christianity and its Bible.

In other words, he’s offended. But why should his sense of outrage be legally significant? After all, every citizen is offended by something the government does, but we don’t have a right to sue because of our offense. In other words, we generally only have a right to sue when a government policy or action violates specific, legally-protected rights. And we do not have a right not to be offended.

Except, of course, when I’m offended by the sight of religious symbols on public land. Most Americans don’t realize this, but past Supreme Courts carved out a special doctrine applicable to public religious expression that enables angry activists to chase religion out of the public square. It’s called “offended observer” standing. In National Review Online, I described the doctrine like this:

One of the most pernicious developments in modern law has been the creation of “offended observer” standing in Establishment Clause cases. Essentially, the Supreme Court has carved out an exception to normal rules of standing (which require a plaintiff to establish a concrete harm to their rights) for the special purpose of challenging any government acknowledgment of religion.

As a practical matter, this has been one of the most divisive and biased procedural elements yet devised in constitutional law. Under this unique doctrine, a few plaintiffs can undo decades of community consensus and rip apart long-standing traditions — not because they have been coerced in any way but simply because they were “offended” when they heard a public prayer or saw a nativity scene on public land.

We’ll be watching the situation closely and render what aid we can, but as you see this and other Establishment Clause cases play out across the legal landscape, remember they exist only because courts have for decades gamed the system to grant special rights to the angry anti-religious activists among us.