“I Came, I Saw, I was Offended” - It’s Time to Finish Offended Observer Standing

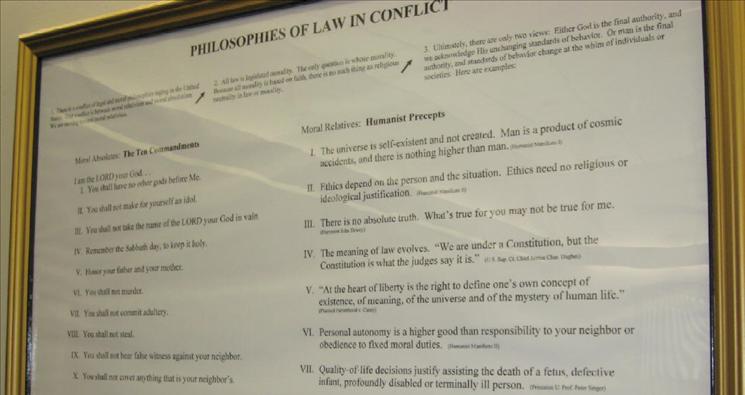

Does the ACLU have the right to sue a judge over his display of the Ten Commandments simply because one of its members finds the display offensive? Does a federal court have the constitutional authority to order the removal of the Ten Commandments merely because an ACLU member finds their public display demeaning?

These questions raise the issue of what’s called “offended observer” standing — an issue at stake in our pending Supreme Court petition in ACLU v. DeWeese. Under this theory, a court has jurisdiction to adjudicate a challenge to a governmental religious display based on nothing more than the allegation that observation of the display causes offense. Groups like the ACLU and the Freedom from Religion Foundation have used this theory to challenge everything from nativity scenes to memorial crosses to Ten Commandments displays. As we wrote in our petition, offended observer standing amounts to little more than “I came, I saw, I was offended.”

The problem with offended observer standing is that it conflicts with a well-entrenched line of Supreme Court decisions. The Court has consistently held that mere ideological disagreement with government action is insufficient to confer standing on the plaintiff or jurisdiction on the court. The reasoning behind this rule is clear: if one could file a federal lawsuit against the government on the grounds of disagreement or offense alone, the courts would be inundated with cases brought by upset and aggrieved citizens. As one federal judge correctly put it, “there would be universal standing: anyone could contest any public policy or action he disliked.” Political and ideological disagreements should be fought out in the legislatures, not the courts.

Not only does common sense require an injury requirement to confer legal standing, so too does the U.S. Constitution. Article III mandates, among other things, that federal courts only rule upon cases or controversies. This means, first and foremost, that the party bringing a case to federal court must be injured in some way. Without an injury, there can be no case; without a case, there can be no decision.

In 1982, the Supreme Court applied the Constitution’s injury requirement in an Establishment Clause case. In Valley Forge Christian College v. Americans United for Separation of Church and State, a church-state separationist group claimed that the federal government’s donation of surplus property to a Christian college violated the Establishment Clause. The Court held that the plaintiffs did not have standing because they suffered no injury. It noted that the “psychological consequence presumably produced by observation of conduct with which one disagrees” does not constitute an injury in any constitutional sense.

How is this not a description of the offended observer?

Despite what the Supreme Court held in Valley Forge, most lower courts have by and large ignored it, or distinguished it away to the point of no meaning. In DeWeese, for example, the district court held that the ACLU had standing to sue Judge DeWeese because an ACLU member said he was “personally offended” by the judge’s display. That’s it. There was no allegation that the display directly or indirectly coerced him to think or act in any particular way, or even that the contents of the display conflicted with his own religious beliefs.

It’s time for the Supreme Court to reject clearly and unambiguously the notion that “I came, I saw, I was offended” amounts to an injury in the constitutional sense. The proper venue for persons offended by what they think to be an improper religious display is with city councils, county boards, and state legislatures — not the federal courts.

Next week, the Supreme Court will consider our petition in ACLU v. DeWeese and decide whether to hear the case. We’ll keep you posted.